VNTNRTM

VNTNRTM

VNTNRTM connects makers drinkers & thinkers in the pleasure of wine

DIRT, BIAS AND CHARDONNAY

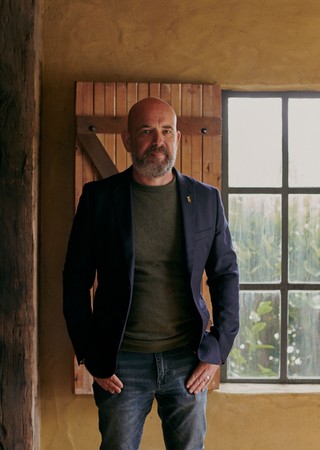

Peter Munro: my name is Peter Munro. I'm the Chief Winemaker for St Hugo.

VNTNR: A Chief Winemaker with unlikely beginnings: as an analytical chemist no less. What are the throughlines between these two fields, shared skills or ways of working?

PM: I studied chemistry at university, and worked for a year as an analytical chemist. I decided very early on that it really wasn't for me, and I was going to get out before I got anywhere. And what appealed about winemaking was this concept of melding science and creativity together. Chemistry is an amazing basis to build a winemaking career on. It is science-based and having that knowledge is really useful. Being technically competent as a winemaker is extremely useful; it's a great bedrock to build upon. I saw winemaking as an opportunity to use some of those skills, but also in a more creative and interesting way for me as a young man a long time ago.

VNTNR: Where do you see the objectivity of science relating to winemaking?

PM: I love the fact with winemaking that there is no right or wrong answer. And what I love about winemaking is as a winemaker, you're part of the process. In science, it's all about being objective and trying to understand a system, and as much as we can try convince ourselves as humans that we stand objectively and we observe, we don't. And with winemaking, we don't even pretend to do that. We are part of the process. And the consumer - the person that tastes that wine at the end of the day - is part of the process. And I love that because it's a holistic way of looking at creating something. And I can have a really positive influence on the wine. I can have negative influence, too (hopefully not very often). The wine in the glass looks - in part - how it looks because of me. And that is really appealing to me. Does that answer your question?

VNTNR: Yes. It seems there’s an element of humility in this line of work, where the reception of the audience plays a crucial role in the experience of the wine. You have to relinquish control at a certain point when people bring their own ideas, experiences and memories into their mouths and blend that into your wine.

PM: One of the things I think it's really important for a winemaker is to have a clear vision of what you want the final product to be. You make so many small decisions in winemaking on a daily basis, that slightly edge you in a direction. And if you don't know where you want to end up, it's very easy to get lost and make a wine that, for the winemaker, lacks a bit of purpose. But I totally agree that once you make that wine, you have a vision and hopefully you create it in the shape of that vision. But then when someone takes it away, and they have it with dinner or they have it with friends, or they have it in a certain situation, it's their wine. They have to interpret it how they want, and their environment will influence how that wine tastes. That's another thing I love about wine; it’s living and it adapts to the environment it's in. The way I perceive a wine - a wine that I made or another wine - will be very different to the way someone else does. And that's great. That's a great conversation starter. That's a way of interpreting the world through wine, as we do through art, as we do to nature. And to be able to create something that can begin that conversation I think is wonderful.

VNTNR: How do you converse with nature in your winemaking?

PM: So when I got into the wine industry, I was lured by this objective of melding science and creativity. What really interests me now is the agricultural aspect and the creative aspect, or the working-with-nature aspect because at its heart, wine and winemaking is an agricultural business. And I love that it’s an agricultural business. We are at the whims of nature. And winemaking is very adaptive; you can't do the same thing that you did last year to make the same wine because nature is different, the seasons are different. The vines, the living vines, have had a different year to create different fruit. Being receptive to that change, being cognizant of that variation, I think is really important to make great wine because as a winemaker, you're interpreting nature. And if you're not aware of those small, small changes, you don't do it justice in my view. And one of the things for me personally that influences the vines and the fruit that comes off them, is the dirt they’re grown in because you can have a vineyard that's 100 meters down the road growing with the same variety, and they'll taste totally different. The general climate might be about the same but the dirt could be very different, and that brings so much character to the grapes. And I like to call it dirt because it's agriculture. We see wine in very rarefied environments and as a society, we give wine a reverence that sometimes it doesn't deserve. But at the heart of it, it's a plant growing in dirt. And that's what gives you the character that makes great wines, what people find fascinating and creates conversations, and makes all these wonderful social interactions possible. And I think it's nice to just talk about the dirt because it reminds people of where this all comes from.

VNTNR: What about the magic in the transformation from dirt to delicious liquid?

PM: Do I see wine as magical? Probably not. But I see wine as living. It changes obviously from the juice that comes out of the berries, and then we work with another living organism, yeast, to create the alcohol. And that is a very symbiotic relationship that needs to be managed really carefully to get the best out of it. And then, as you have wine and we age wine in the winery before most people see it, it changes dramatically. And then we often put different parcels of wine together and blend them, and that changes the wine dramatically as well. You can really alter the style of a wine by using different parcels together, which is one of the most fascinating parts of winemaking because you think well, I'll just pick the best five parcels and I'll put them together and that'll make the best wine. That's not how it works at all, and that's the fun thing about blending. Because you can have an idea about what a parcel might bring to the blend, and start on that path of putting them together and tasting them together but you don't really know until you put them together on the bench and you taste them. And it's not in any analysis to say that this is going to be the best wine; it's what you taste in the glass. And this is where it comes back to being an interpretation.

We're very lucky at St Hugo that we have a group of great winemakers, and the discussions that produces about what's the best wine or what's the style of wine we want this to represent, are some of the funnest and most engaging parts of my job; being in those conversations with people talking about what they're tasting and why it's better or why it represents what we're trying to do. Then you put wine into a bottle and some people - those lucky people that can afford to put it away and not drink it and forget about it - taste it when it's 5, 10, 15, 20 years down the track. The wine changes and it doesn't make it better, it doesn't make it worse, but it changes. And I love the fact that that's what wine does. So I don't think it's magical, but I think it's evolving and it's alive.

VNTNR: How do you make a wine that’s suited to ageing, or as you put it, being alive for so long?

PM: I'm very fortunate to look after St Hugo as a brand, and the history and the provenance of St Hugo has always been about making wines that will age gracefully over that 10, 15, 20 year period. So when we bring in our Coonawarra Cabernet, every decision from when we harvest it to how we ferment it, to how we age it, to how we blend it, is about upholding that tradition. And the decisions we make for those wines would be very different from the decisions we'd make for a wine you’d want to release when it was six months old and drink that same year. So it gets back to the vision that you want for the final product. And it changes depending on what the final product is. With St Hugo it’s very much about that. I also believe that a wine that will look great in 20 years time, looks great throughout that whole 20 year period. I mean, in my opinion, you don't make wines that suddenly become awesome when they're 20 years old. They're good when they're one year old. They're good when they're three year olds and five year olds. But the vision of how that wine should end up in it's evolving, is in that 20 year period. And that's our vision. That's what we see as St Hugo.

VNTNR: We’re talking about 20 years ahead now. What about 20 years back?

PM: Do I value the same characteristics in wines that I enjoy drinking now as I did 10, 15 years ago? No, definitely not. Things that I like to drink now are very different from what I wanted or liked to drink 10, 15 years ago. My preferences, my biases have changed and they probably will change again, too. But I don't think that's a bad thing. I think that's just evolving.

VNTNR: What wine are you enjoying at the moment?

PM: The environment dictates what I would like to drink. If it was kind of a nice day, pretty casual, one of the things I really am enjoying at the moment is Australian Chardonnay. Australian winemakers across numerous regions are doing exceptional things with Chardonnay and making what I consider are world class Chardonnays. And it sounds very boring but we have an outdoor oven at home that’s woodfired, and if you cook a roast chook in that with the potatoes soaking up all the smoke and everything, and then you have a five, six year old Australian Chardonnay; it doesn't get much better than that. So that's one example. But there's many examples of things that I'd love to drink. And hopefully, there'll be many more.